Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt

This is a talk about the world we live in. One which sees us becoming increasingly reliant upon a small number of web services and the companies that operate them, most of which emanate from a small centre of innovation: Silicon Valley.

Much of what I’m going to say tonight could be described as pure FUD – cynical nonsense and fear-mongering. Yet fear, uncertainty and doubt – these are real human emotions that can be too easily brushed aside in the face of valid concerns or criticism.

We have entered into relationships with powerful organisations. These are organisations we will declare our undying love for, but I want to question whether we’ve taken the time to consider the consequences of doing so.

I fear for the future of the World Wide Web.

Tim Berners-Lee’s invention promised us great things, not least a highly democratic communication tool in which anyone could access information, and anyone could publish information. It’s a powerful concept, and it’s one we shouldn’t lose sight of.

That it’s been hijacked by commercial interests shouldn’t surprise us, but the way it’s been hijacked should. Not only is our behaviour constantly monitored and tracked, sites like Facebook, Google+ and Twitter are actively manipulating our behaviour as well.

In an article entitled Modern Medicine, Jonathan Harris described social software design. He wrote:

The designers of this software call themselves “software engineers”, but they are really more like social engineers. Through their inventions, they alter the behaviour of millions of people, yet very few of them realise that this is what they are doing, and even fewer consider the ethical implications of that kind of power.

On a small scale, the effects of software are benign. But at large companies, with hundreds of millions of users, something so apparently small as the choice of what should be a default setting, will have an immediate impact on the daily behaviour patterns of a large percentage of the planet.

At Facebook, for example, they use a term called “Serotonin”, which refers to the bonding hormone released by the brain in moments of intimacy. In design reviews, Facebook designers are asked, “Where is the serotonin in this design?” meaning, “how will this new feature release bonding hormones in the brains of our users, to keep them coming back for more?”

When seen in this context, you wonder how entities like Facebook are able to operate without any degree of oversight. Is it right that one company can affect the lives of so many people, so freely? Facebook’s leadership may say they are being disruptive; challenging social norms.

The original meaning of a disruptive company was one that used its small size to shake up a bigger industry, but disruption is turning into something more sinister. Reporting on last year’s TechCrunch Disrupt conference, Paul Carr wrote:

The conference stage was filled with brash, Millennial entrepreneurs vowing to “Disrupt” real-world laws and regulations in the same way that me stealing your dog is Disrupting the idea of pet ownership. On more than one occasion a judge would ask an entrepreneur “Is this legal?” to which the reply would inevitably come: “Not yet.” The audience would laugh and applaud.

In the real world, regulation is recognised as an essential part of well-functioning economy, to combat excessive behaviour, and maintain a level playing field.

In the UK we have organisations like the Food Standards Agency and Ofcom. Even America, which has very conservative economic policies, has similar oversight agencies.

The web however goes largely unregulated, which is why it has become so attractive to believers in the free-market and those that have little time for anything that gets in the way of them increasing their personal wealth.

I probably have an unhealthy interest in Silicon Valley, having worked for there a few years ago.

As such, I know a number of people who work in the Valley who are as equally disturbed by these developments as I am. It gives me hope to know that sensible people work there. Obviously, as these people are my friends, they are a self-selecting group, people roughly the same age as me, who share similar interests and political views.

I honestly don’t know what the general attitude is. For example, do most developers and engineers have a moral compasses? Are they able to provide enough of a counterbalance to CEOs like Mark Zuckerberg who have very specific and controversial views on privacy? Are engineers that care about privacy able to find work at these companies?

Put more simply, is the technology sector able to effectively regulate itself?

While the Edward Snowden leaks have been disturbing, I find it hugely encouraging there was someone working for the NSA that had the moral integrity – and courage – to leak this information. My hope is that there are others like him.

I am uncertain that having Silicon Valley be the home to so many of the services we use every day is that healthy.

On a superficial level, I’m not sure Silicon Valley has a healthy culture of design. To me, it appears to be seen as a mean of styling, or manipulating, but not to producing things of any inherent value.

Many of the companies have strong engineering-biased cultures, and there is an over-reliance on seeing customers as little more than data-points.

On leaving Google, Doug Bowman famously wrote:

A team at Google couldn’t decide between two blues, so they’re testing 41 shades between each blue to see which one performs better. I had a recent debate over whether a border should be 3, 4 or 5 pixels wide, and was asked to prove my case. I can’t operate in an environment like that. I’ve grown tired of debating such minuscule design decisions.

He was of course referring to Marissa Meyer. When not wanting to test which shade of blue to use at Google, she went on to design Yahoo’s new logo, with somewhat predictable results.

Is it not interesting that a lot of identity work emanating from the valley is rationalised with circles and lines overlaid? Is this the only way designers can justify their work?

How prevalent is this thinking within the Valley. Is it confined to Google?

Yet more importantly, these companies are founded and operate under US law, which is very different from English and European law.

Charles Stross, writing in 2011, noted that the California-based web service Klout had a privacy policy that was almost certainly illegal under the UK Data Protection Act, not least because they asserted the right to collect information about you, if you simply visited their website.

Perhaps more damaging is the lifestyle to which engineers at well-funded start-ups are able to enjoy.

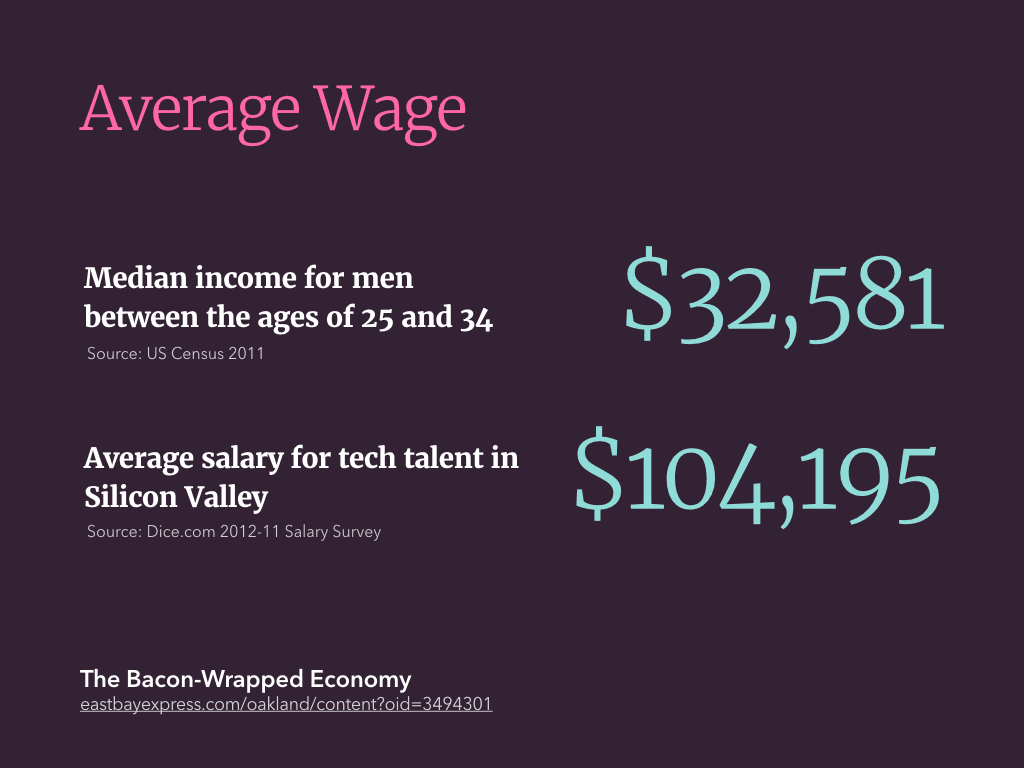

According to the US census in 2011, the median income for a man between the ages of 25 and 34 was just over $32,000. Yet according to recruitment site Dice.com, the average salary for tech talent in Silicon Valley was more than $100,000. (Source)

This is something I can recognise. When I joined Ning, I was flown over to Palo Alto, put up in expensive hotels, and had the rent paid for my apartment. Meals were often brought in every lunchtime, and the fridge was always stocked full of treats. And yes, I had an outrageous salary too.

It was lovely to be treated so well, although I always felt there was an underlying motive; a desire for you to never leave the office, or spend any of your free time not thinking about work. This was particularly evident when I was offered a MiFi dongle and data contract, so I could work on the train to and from the office. Weekends felt like a privilege, not a right.

Is this just a symptom of the broader American work-ethic?

You can argue the merits for and against employees of large tech firms being rewarded so handsomely, as much as you can for footballers and bankers. A shortage of talented engineers and designers means rewards will be high. But I wonder if this is creating an environment in which the people building products we use every day have little empathy for how the rest of us live.

In her article Silicon Valley’s Problem Catherine Bracy articulates the problems associated with this bubble:

The well-documented lack of diversity in the Valley would be comical if it wasn’t so harmful. It feels like, and often is, a bunch of Stanford guys making tools to fix their own problems. Sometimes they stumble into a groundbreaking new app that has a more far-reaching impact (see: Twitter) and sometimes they try and shoehorn a social good mission into their business plan (see: a thousand other companies). Barely any of them start from an entrenched social problem and work backwards from there. Very few of them are really fundamentally improving society. They’re making widgets or iterating on things that already exist.

Here in lies the opportunity. There are very few technical constraints forcing companies to relocate to the Valley anymore. Companies that exist outside the bubble have a greater chance I believe of designing products more empathetic to the wider world.

Funding may still be an issue, but governments and local authorities are seeing growth in the technology sector and want to support it. Not having the culture of well-funded venture-backed start-ups will lead to the creation of more sustainable businesses too.

My good friends at Lanyrd are wonderful proof that you can build a successful start-up outside the Valley.

However, I worry that there is a desire to replicate Silicon Valley, which is a futile endeavour; Silicon Valley is the result of a century of good fortune and happy accidents. Digital hubs should be true to themselves, not facsimiles of a rotting model.

I doubt many of us really think about the amount of trust we place in the small number of services on which we rely on a daily basis.

I host all my photos on Flickr, but why have I decided to trust Yahoo!, a company that has consistently proved itself a poor custodian of user data, not least when it deleted the 38 million pages it once hosted on Geocities.

Yahoo! is not alone in exhibiting such behaviour. Myspace recently deleted all the blog posts once hosted on its platform, providing no warning that it was going to do so. Individual posts or sites have been taken down on Tumblr without warning because of DMCA take-down notices, or legal disputes, with little or no recourse for content owners.

We’ve come to rely on these services so much that there’s an implicit trust in the companies that operate them. Do they deserve our trust?

Smaller start-ups are worse of course, especially at the moment they get acquired.

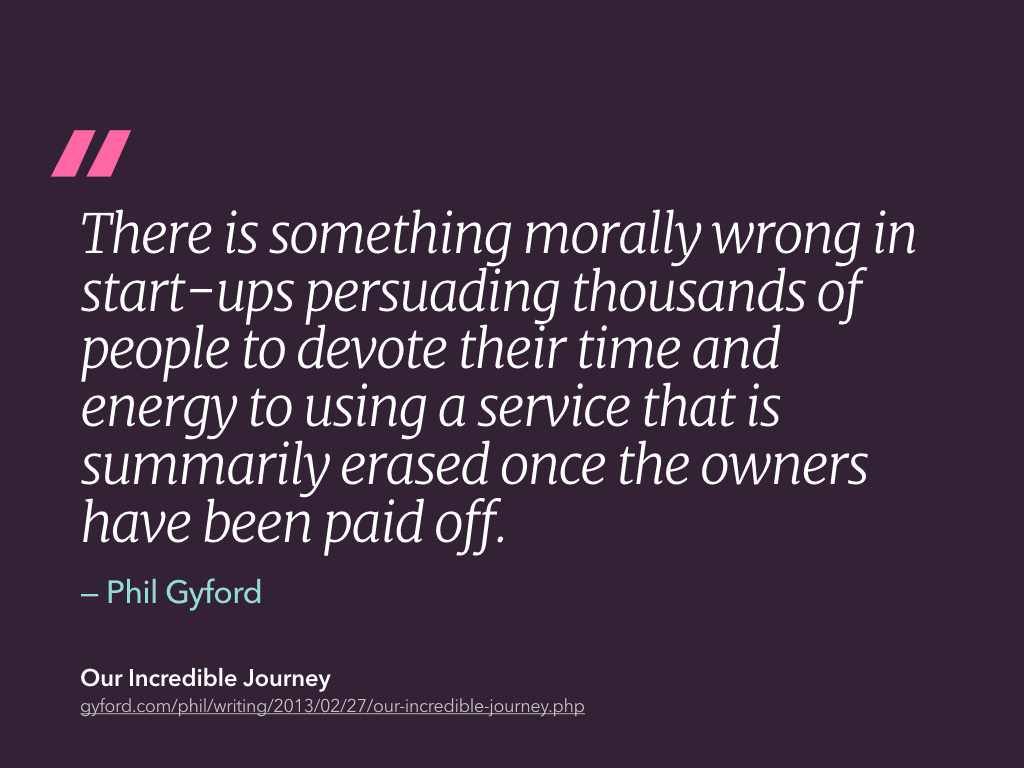

Phil Gyford has been curating a blog listing companies blog posts in which they exclaim their excitement of being acquired, and the inevitable posts that follow a few months later which backtrack on any promises regarding content users have uploaded.

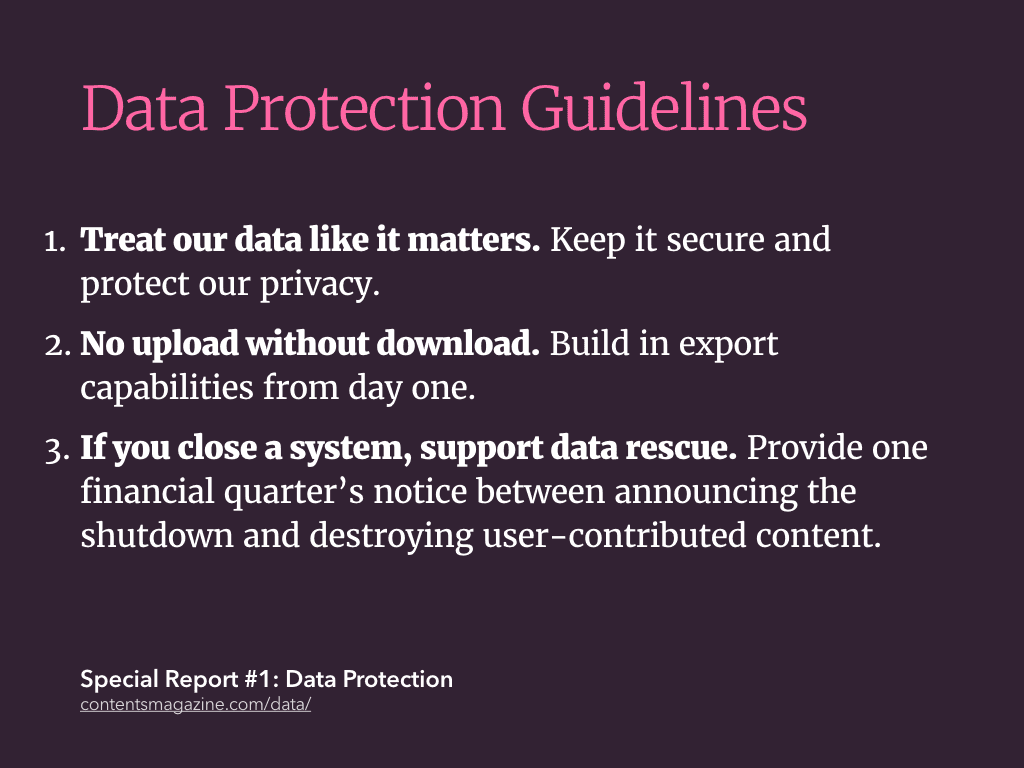

In its manifesto for how companies should treat our data, Contents magazine suggested all services should:

- Treat our data like it matters: Keep it secure and protect our privacy, of course – but also maintain serious backups and respect our choice to delete any information we’ve contributed.

- No upload without download: Build in export capabilities from day one.

- If you close a system, support data rescue. Provide one financial quarter’s notice between announcing the shutdown and destroying any user-contributed content, public or private, and offer data export during this period.

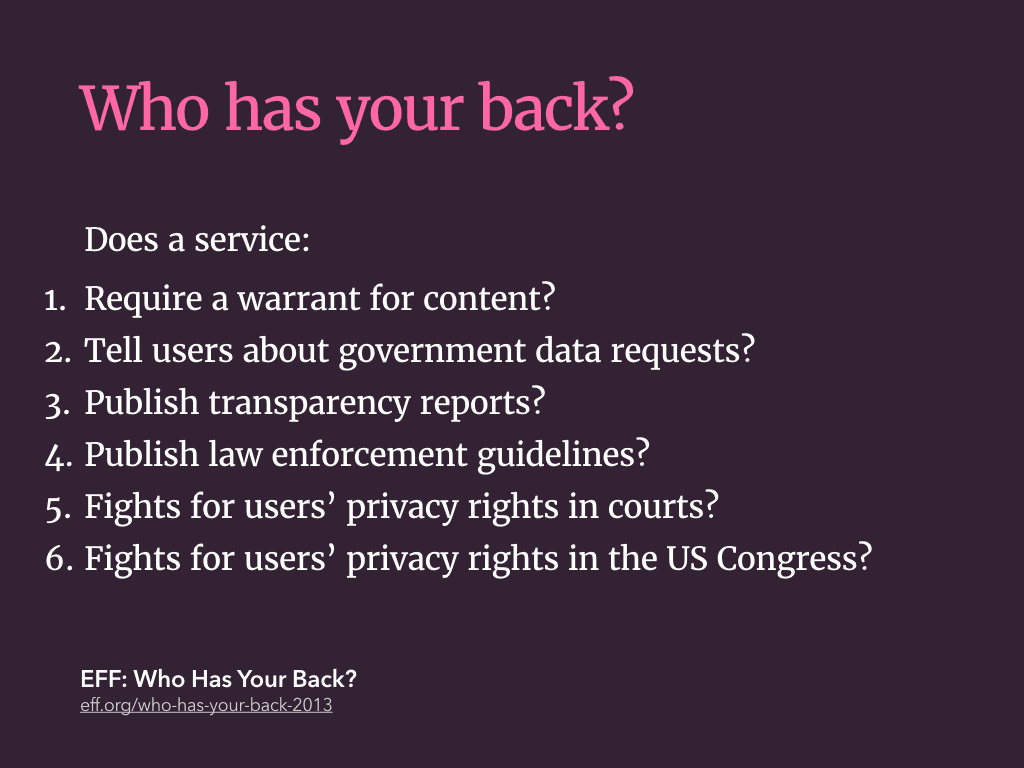

In a similar vein, the Electronic Freedom Foundation conducts an annual survey in which it measures how well companies protect your data from the government. It has six criteria.

Of the big internet services, only Twitter scored six stars out of six. Apple got one. This year’s survey was conducted before the Snowden leaks, so it’ll be interesting to see how these ratings change. However, since the EFF started publishing this report two years ago, the scores have been improving.

I think it’s important to recognise, that as early adopters of a lot of these products, we wield excessive power. We shaped products like Twitter, and we can shape future products too!

Rather than gush about the design of a new service, we should congratulate services on well-written terms and conditions, data export options, how well they protect us against government snooping.

If they don’t treat us with respect, we should choose to use a competing service.

It’s easier to change services if you own and control your own data. The nascent Indie Web movement promotes publishing content on your own site, and optionally syndicating it to the third-parties.

Earlier this month, I went to Indie Web Camp. This is an event where people are creating new technologies, products and protocols that allow us to do just that. While a lot of the concepts being demoed were still in development, I was impressed by the focus on making these new tools user-centred, and in many cases, better designed than the products they are attempting to replace.

There is also a good deal of pragmatism running through this initiative; many of the contributors realised that the best tools for creating this content were built by the third parties, but we can use their tools, and then store the definitive copies on our own servers.

I think we have reached a pivotal point in our use of web-based services, and now face a fork in the road. We have two choices:

- We continue to let our lives be governed by a few powerful companies, and accept the consequences this brings.

- Or, we start to take back control of our data, and control of the web.

I’m sure, like many of you, the recent revelations about mass online surveillance undertaken by the NSA and GCHQ have made using the internet less exciting than it used to be. Not least because the companies running the services we have come to rely on appear to have been complicit in aiding these programmes.

Thankfully, everyone in this room has the ability to make a difference, to build the web we want to see. Although the web has matured considerably in the last 20 years, a text editor, an FTP client and some web space is all you need to publish on the web.

I’ll leave you with a quote from Bruce Schneier, from this article in the Guardian:

…we built the internet, and some of us have helped to subvert it. Now those of us who love liberty have to fix it.