London’s Olympic Stadium: A Legacy Lost

The Olympic Stadium nearing its completion in 2012

The history of the Olympics is not only one of remarkable sporting achievement, but acts of incredible artistry too. Over nearly 120 years, organisers have commissioned beautiful works of graphic art – Lance Wyman’s celebrated identity for Mexico ‘68 and Otl Aicher’s timeless design for Munich ‘72 immediately spring to mind – and also staged captivating acts of theatre. Zhang Yimou’s immense opening ceremony in Beijing and Danny Boyle’s more modest but no less emotional tribute to British invention and social progress in London, are just two recent examples. As for interactive design, well that’s another story.

The most notable creative output is that of the architecture, with each games requiring large venues to host the almost 30 different competitions held over the course of two short weeks. With organisers using the Olympics to promote national identity and regenerate deprived areas, it is these impressive yet expensive amphitheatres that attract the most attention and controversy, none more so than the centrepiece Olympic Stadium.

Beautiful white elephants

Atlanta, host city of the centenary games of 1996, is considered one of the least successful outings for a summer games, especially given its overly commercialised atmosphere. Yet long before ‘legacy’ had entered the Olympic vernacular, organisers had displayed incredible foresight regarding the future use of their venues. Here, the stadium was destined to become a baseball arena, and no sooner had the Paralympics finished, the track was uplifted, the temporary seating demolished, and the Centennial Olympic Stadium became Turner Field. What seemed like an unsympathetic move at the time, was in fact an impressive act of pragmatism.

Other hosts have not been so thoughtful. So complex was the design of Montreal’s Stade olympique, that it was left unfinished during the 1976 games, and completed nearly a decade later. In fact, it became one of the most expensive stadiums ever built, its retractable roof failing to account for the city’s brutal winters and needing constant repair. Publicly financed to the tune of CAD$ 1.47 billion, the total cost was finally repaid in 2006. No wonder residents call it The Big Owe.

The distinctive shape of the Olympic Stadium in Montreal, its observation tower a constant reminder to residents how much it cost to build. Photograph: Maciek Lulko

A few cities have bucked this trend – Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and Berlin’s Olympiastadion, both built early last century, remain in use today – but modern stadiums, such as those in Beijing, Sydney and Barcelona, struggle to find tenants or attract huge audiences. Athen’s venues, another victim of that country’s wider economic tragedy, stand as white elephants, neglected and dilapidated.

London’s plan

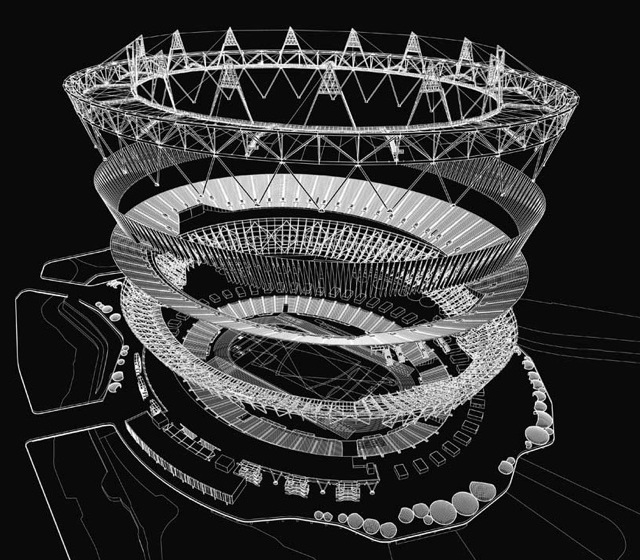

Exploded view of the Olympic Stadium’s construction, showing the permanent and temporary components of its design

Organisers of London 2012, with aborted attempts to build a national athletics stadium at Picketts Lock and Wembley fresh in the memory, hoped to learn from these mistakes.

They decided to build a venue with a modest legacy: that of a small 25,000 seater athletics venue. A temporary upper tier was built to accommodate a further 55,000 spectators during the games, but this would be dismantled soon afterwards.

Two events conspired against this vision.

4 May 2008. With designs finalised and construction under way, Boris Johnson succeeded Ken Livingston as Mayor of London. Unlike his predecessor, he wanted to retain a venue with a high capacity after the games, which meant securing a Premier League football club as a permanent tenant.

4 August 2012. Day 8 of London 2012, and Great Britain’s most successful day at an Olympic Games since 1908. Soon dubbed ‘Super Saturday’, it culminated within the space of 46 minutes with Jessica Ennis, Greg Rutherford and Mo Farah each winning gold medals at the stadium that evening. These achievements, days after the country had been emotionally cajoled by Danny Boyle’s heartwarming opening ceremony, meant the stadium was seared into the country’s consciousness. Dismantling what had become an iconic venue, seemed unthinkable.

Jessica Ennis celebrates winning the women’s heptathlon during ‘Super Saturday’. Photograph: Al King

Rectangle pitches, oval tracks

Football stadiums grow ever larger, as wealthy club chairman look to increase ticket revenues and satisfy fans’ appetite to watch games played during 10 month-long seasons. In order to create a hostile atmosphere for visiting teams, the best grounds feature steep terraces that impose onto the field of play.

Funding for athletics is primarily sourced from government and lottery grants. Meets take place during the summer, attract fewer spectators, and the nine lane 400 meter oval running tracks positions spectators away from the infield.

Put simply, football stadiums (or those for rugby, baseball or other pitch-based sports) have vastly different requirements than those designed for athletics. That is why football teams avoid playing in multi-purpose stadiums: having terraces set so far back from the pitch can result in poor sightlines and a diminished atmosphere. In 2005, Bayern Munich left the Olympiastadion and moved into the purpose built Allianz Arena, while in 2006 Juventus demolished the Stadio delle Alpi and replaced it with a stadium of their own design.

Yet the centrepiece of the world’s largest multi-sport event asks that organisers solve this conundrum: build a vast stadium that can host athletics for two weeks, yet have it remain useful for many years afterwards. Build and forget, or build and convert?

So good, they built it twice

With previous legacy plans discarded, the Mayor’s London Legacy Development Corporation decided to convert the stadium so it could host football, and selected West Ham United as its permanent tenant. To ensure the stadium was more suited to pitch-based sports, architects made a number of changes, including designing a roof that could cover retractable seating on the lower tier. Extended, these seats would place fans closer to the action and protected from the rain.

An imposing new roof hangs above the seating bowl that was meant to be temporary. Photograph: Andy Hall

Attending a seminar at the Institution of Structural Engineers, I learnt about the design of this new roof in great detail. The original installation – intended not to shelter spectators, but to ensure records set on the track remained legal and not wind assisted – could conceivably have been doubled in size to cover seats in lower bowl. However, to cover the retractable seats, the roof neded to reach much, much further. To achive this, they constructed the largest spanning tensile roof in the world. Weighing almost 6000 tonnes, existing supports needed to be strengthened and replaced to carry this additional load.

It wasn’t until I read Owen Gibson’s article in the Guardian, that I recognised the delicious irony at the heart of this redevelopment (emphasis added):

The £272m conversion (not far off the £280m the stadium was originally slated to cost) is all but complete and the effect is at once impressive and disconcerting. Nothing has changed and yet hardly anything remains the same. The triangular floodlights have been removed and apparently inverted (they are in fact new structures, though the light fittings have been retained). The only part of the stadium that remains is that which was supposed to be temporary (the upper tier), while the section that was to be permanent has been replaced (the bottom tier, swapped for new retractable seats).

The few other remaining elements of the original stadium will soon disappear as well. The distinctive seating pattern, whose fragment design features lines that converge on the finish line, will be replaced with a design that suits West Ham United’s own tastes. The red Mondo track is to be ripped up and replaced with a new blue surface. Even the name is likely to change, with operators looking to sell naming rights.

London’s first Olympic Stadium, The Great Stadium, was built in White City for the 1908 games and demolished in 1985. What does the future have in store for the stadium in Stratford? Photograph: © Museum of London

Wanting to see the redeveloped stadium close-up, I attended last weekend’s London Grand Prix (or ‘Anniversary Games’). While the new roof is impressive, it’s somewhat undermined by the structure it sits on. As it rises slightly as it approaches the central tension ring, and without the upper seating bowl being hidden from view by the outer decorative wrap, from a distance it looks as though a UFO has landed and is being held down with scaffolding.

Visiting the stadium in athletics mode, it’s hard to judge what it will feel like when playing host to football matches. Given the shallow pitch of the seating, the large gap between the top and bottom tiers, and the space set aside for large screens, I doubt the venue will provide the fortress-like atmosphere West Ham fans are hoping for. The first test of this configuration will come during the Rugby World Cup matches being held later this year.

While a future for the venue has been secured, it has come at a considerable cost – and with much obfuscation of the fact that tax payers have effectively paid for two stadiums. If I were to make a prediction about its medium-term future, I’m not sure it would involve West Ham United, even if they have effectively been gifted a publicly subsidised ground. Still, at least London now has a semi-permanent athletics venue, and one capable of holding the World Championships in Athletics in 2017.

Lessons ignored

This takes place within a broader context, one in which similar mistakes continue to be made around the world. Only this month, the Japanese government scrapped plans to build Zaha Hadid’s controversial Olympic stadium in Tokyo. Organisers might have been tempted to revert back to earlier plans which involved upgrading the stadium used during the 1964 games… except this has been demolished to make way for the new one. You couldn’t make this stuff up.

Zaha Hadid’s controversial design for Tokyo’s new Olympic Stadium. Render: © Zaha Hadid Architects

Meanwhile in Europe, with the continent emerging from a deep recession, there are signs that organisers are considering others means of hosting events without erecting costly new venues. The Commonwealth Games in Glasgow saw the national football stadium at Hamden Park temporally converted to an athletics venue; the raised field sat upon a series of stilts, covering the lower tier of seats is remarkably similar to the compromise arrived at for the new Wembley stadium. Euro 2020 will be hosted across multiple nations as a one-off event to celebrate the 60th birthday of UEFA. This will be held in 13 host cities, with all but three using existing stadiums (Saint Petersburg’s having been built for the 2018 World Cup).

Elsewhere, the temptation to build grandiose new structures remains, with little thought given to their use afterwards. Nations like Russia and regimes in the Middle East, using international sporting events to project their apparent supremacy, are happy to spend billions on expensive amphitheatres (and often on the back of slave labour and human rights abuses).

It would have been awful to see the Olympic Stadium in Stratford dismantled, yet by reneging on earlier legacy commitments, London missed an opportunity to set an example for future organisers. Yet had it done so, would it have made any difference? If the story of Olympic stadiums proves one thing, it’s that pride and politics are often the enemy of common sense.